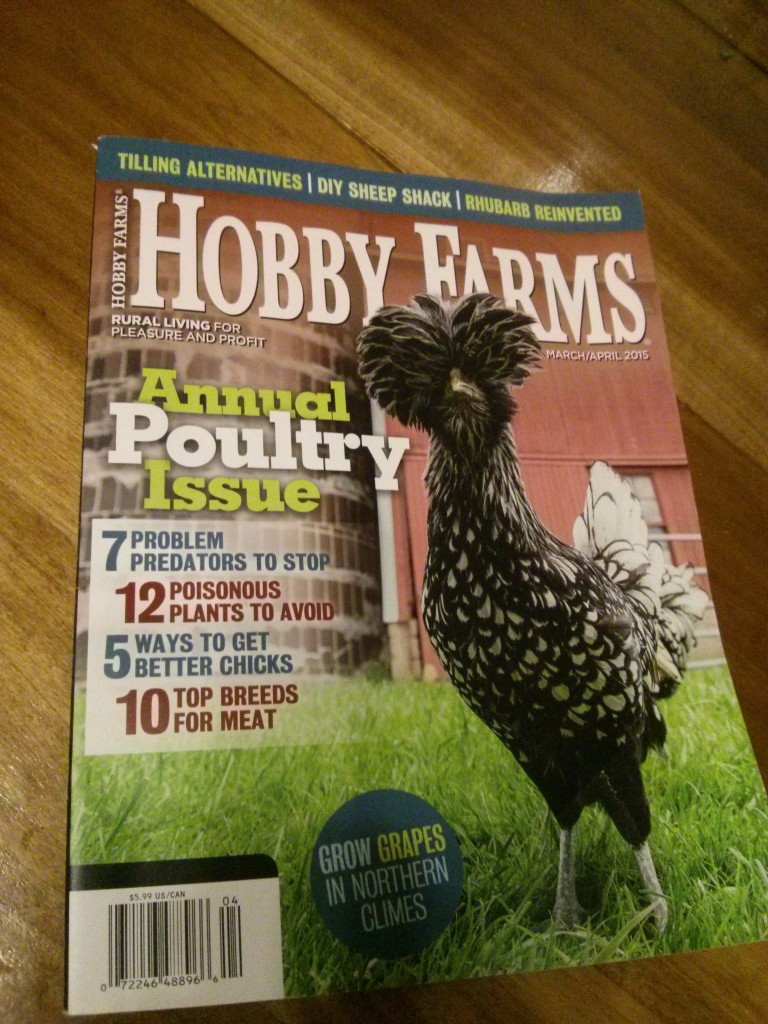

I just got this in the mail and couldn’t figure out why they’d sent me a copy.

I didn’t remember subscribing to Hobby Farms magazine, but something seemed a bit familiar.

It took me a day or two, but I finally remembered a string of emails from a few months back…

Turn to page 40, and yup. That’s me.

A Case for Hybrids

By Leslie J. Wyatt

Some people feel–and very strongly–that perpetuating White Cornish Cross genetics is

unethical. How can it be okay to breed animals whose quality of life is such that they practically

eat themselves to the brink of death, lack the ability and/or the drive to stir far from the feeder,

and who are stressed by such normal occurrences as summer heat? In the quest for a better meat

chicken without the drawbacks of the Cornish Cross, some farmers are experimenting with their

own hybrids, and Andrew Johnmeyer of Green Machine Farm in Zumbrota, MN is one of them.

When asked what would be the advantage to creating your own hybrid strain, Johnmeyer, who

grows pastured, humanely-raised poultry, beef, pork, and produce says, “The main advantage is

that you can control your genetics, much like you can when raising pigs or cattle. For raising

birds on pasture, you can select for traits that benefit you like heat and cold tolerance, foraging

ability, etc. I look for the same traits that chicken producers have been looking for for the past

100+ years: growth rate, muscling (especially in the breast), white feathers, white skin and low

sexual-dimorphism.”

On Green Machine Farm, which sells to consumers, Johnmeyer has raised Cornish Cross,

Freedom Ranger (aka Red Ranger, Rainbow Broiler) and his own hybrid created by crossing

White Orpington with Dark Cornish heritage breeds. His hybrids turned out to be far too slow

growing to be economically feasible. He also adds that it takes a lot of time and energy to raise

your own successive generations of meat chickens. “Hatching successfully can be a real pain at a

small scale, and for most working farms the opportunity cost is just too high to justify raising

your own chicks.” He goes on to say, “I find that it’s far easier to sell the Cornish Cross because

it’s what consumers are used to eating. The customers who have tried our Rangers and Hybrids

have loved the flavor, though some have had difficulty adjusting to the differences in cooking

that are required for an older bird.” He advises that whatever you choose to raise, it’s very

important to communicate the differences (good and bad) to the consumer so that they can

manage their expectations. Johnmeyer does like the explosive growth of the Cornish Cross and

their near universal availability. “They grow out very quickly and you never have to look far to

find Cornish Cross chicks.” However, he adds, “I really dislike a few “side-effects” of their

explosive growth. They drink a lot of water, much more than any other breed of chicken. In a

pasture-raised situation it can be a challenge to keep them adequately watered in hot weather. As

a consequence of their high water intake, they create a lot of manure that can be a big problem

when they are in the brooder.” Because of this, they are the most challenging breed to keep in

dry bedding, as they will soil it far quicker than other breeds.” the toll that this explosive growth

takes on their bodies and behavior. In addition to the aforementioned leg and cardiovascular

problems as their muscle-growth outstrips their organ and skeletal growth, Johnmeyer says,

“They are also much more vulnerable to changes in environmental conditions. Hot days, cold

nights and even being moved on pasture can kill them.”

Johnmeyer states that he has liked raising the Rangers the most, as they combine most of

the convenience and growth of the Cornish X with the pasture-suited traits and low mortality of

the heritage breed chickens. “The law of diminishing returns is very applicable to raising

chickens on pasture. Just taking a Cornish Cross out of the broiler house and raising it on pasture

results in a huge improvement in flavor and texture. You can keep improving, but it comes at an

ever-higher cost. Alternative broiler breeds are more expensive (mainly due to the increased time

it takes them to mature) but they will taste better still. Past that, I haven’t found breeding our own

broilers to be an economically feasible option.”

It’s nice to have one of my complete failures (the homegrown hybrids) immortalized in print.

Awesome!

That’s really cool, I can’t wait to learn more this summer!!!